What Went Wrong at the 2025 World Ramen Festival in Busan

The 2025 World Ramen Festival in Busan promised global flavors and social impact — but visitors found disarray, broken promises, and little more than lukewarm noodles.

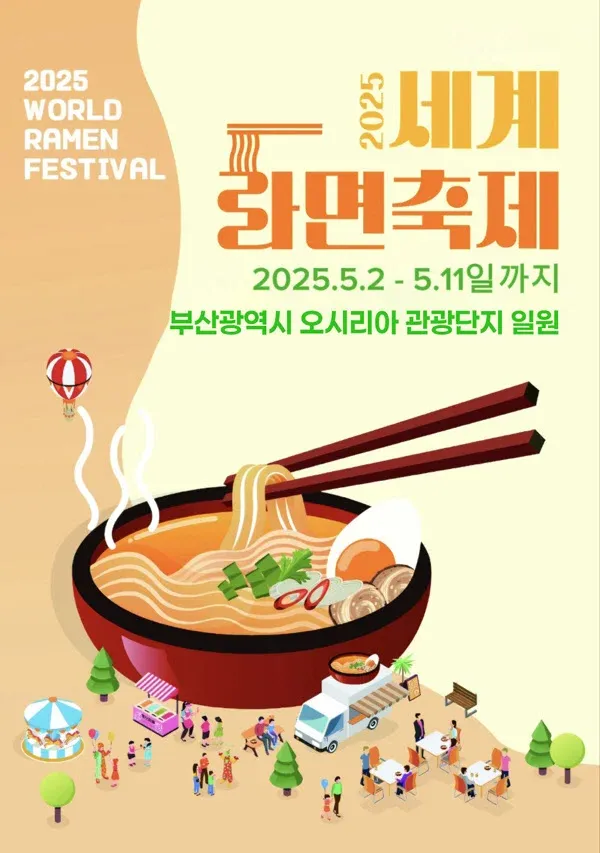

Busan, South Korea — Billed as a celebration of ramen, community, and climate action, the 2025 World Ramen Festival promised much more than food. Posters and press releases painted it as a “clean festival,” a global culinary experience with a conscience. But for the thousands who showed up expecting 3,500 varieties of instant noodles from 15 countries, it quickly became clear that this was not the event they had imagined.

Within hours of its May 2 opening at the Osiria Tourism Complex in Busan, the festival was facing harsh criticism. The venue was dusty, unfinished, and poorly equipped. Hot water dispensers failed, booths were disorganized, and ramen options were surprisingly limited. By the weekend, online ratings had plummeted and attendees were comparing the experience to a "₩10,000 disaster."

The festival was launched with high ambitions. Organisers, working in partnership with a local federation for disability support, presented it as a convergence of food, sustainability, and social outreach. Visitors would cook international ramen themselves, enjoy tech-driven contests like an AI-powered karaoke show, and vote on the best noodle brands — whose products, they were told, would be donated to disadvantaged communities.

Press materials declared it a “Clean Festival,” promising eco-conscious sanitation and a donation of ₩200 million worth of ramen. Some media outlets heralded it as a milestone in Busan’s journey to becoming a global cultural city.

When visitors arrived, the reality bore little resemblance to the glossy promotions. The venue, more gravel pit than global showcase, lacked basic infrastructure. Booths were sparsely set, signage was inconsistent, and the main attraction — the ramen — was served with neither clarity nor care. Hot water was unavailable or tepid; preparation areas were few or non-functional.

Images quickly spread across Korean social media. A child holding a dry cup of noodles became the symbol of widespread disappointment. Attendees described empty shelves, limited ramen options, and long waits for basic amenities. Families and groups left early, while others described the experience as “a refugee camp — but with an entry fee.”

By the second day of the festival, word-of-mouth had turned toxic. Online forums and local communities warned people to stay away. Some ticket holders attempted to resell their passes. The event's carefully crafted image was unraveling in real time.

As criticism surged, the festival’s organizers remained silent. No public apology or explanation was issued. The official website stayed unchanged, and the social media channels — once vibrant with promotional content — went quiet.

The city of Busan, which had been prominently featured in the event’s marketing, distanced itself from the controversy. Officials clarified that the city had only endorsed the concept as part of a broader tourism initiative. But many noted that even passive endorsement from public institutions can lend legitimacy — and, in this case, misplaced trust.

The lack of accountability frustrated many. “You can’t borrow the language of sustainability and charity without backing it up,” one local journalist wrote. “It makes people doubt all future efforts that do mean well.”

The Busan World Ramen Festival launched with admirable goals, blending local culture with global themes such as climate action, inclusivity, and poverty alleviation. At the opening ceremony, organizers donated ₩100 million to the Busan Association of People with Disabilities and distributed ₩100 million worth of ramen to 16 district-level disability groups. Local company Muhak also contributed ₩10 million worth of noodles, reflecting a shared commitment to community support.

But these gestures were overshadowed by on-the-ground failures. Operational mismanagement — from unclean facilities to poorly coordinated logistics — exposed a gap between intention and execution. The festival ultimately became a lesson in the risks of branding without infrastructure.

Still, the event deserves some credit for attempting to align entertainment with social value. Its fresh approach offered a glimpse of what culturally conscious festivals might look like in Korea. But to earn lasting trust, future events must invest in systems, planning, and transparency — not just slogans.

The festival became a reflection of a deeper challenge in modern event culture. Ambitious messaging must be matched by meaningful delivery. What could have been a quirky, globally inspired celebration turned into a cautionary tale.

For Busan — a city seeking international recognition and preparing to host larger global events — the incident raises difficult questions. And for audiences everywhere, it’s a reminder: credibility isn't claimed through promises, but proven through action.

As one attendee said, holding a cold cup of instant noodles: “They said it was about the world. But it barely handled the basics.”

Comments ()